December 2018

Centre pivot irrigation is the main method of irrigation for the production of crops and other agricultural products in many parts of South Africa. This great diversity of crops, including winter cereal crops, are found in areas within most of the major irrigation schemes in South Africa.

These are characterised with water stored in the major dams coupled with the delivery of water controlled by canal systems to each adjoining farm. For instance, the irrigated areas in the Orange River basin cover about 222 000 hectares using 2,365 million cubic metres of water per annum.

Runoff water stored in smaller private dams and water from rivers make up the balance and different irrigation systems varying from moved pipe and sprinklers, under ground grid, drag line, wheel move as well as the use of smaller centre pivots.

Crops under irrigation

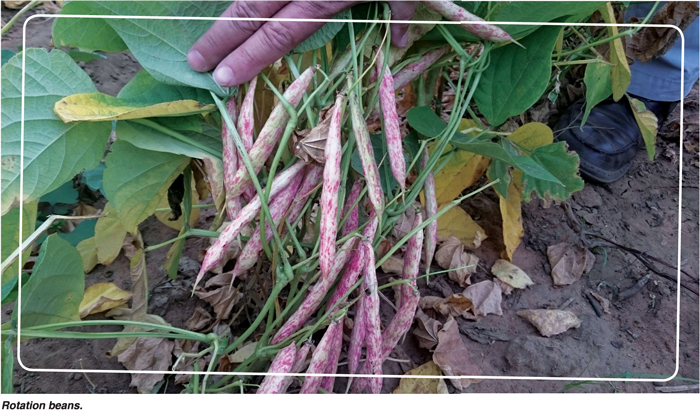

The different crops found under irrigation, under the above schemes, include maize, ‘popcorn’ maize, wheat, barley, dry beans, potatoes, sunflowers for hybrid seed, sunflowers for commercial bulk delivery, soybeans, groundnuts, various pastures, lucern, cabbages, table grapes, apples, other fruits, wine grapes, grapes for raisins, deciduous fruit and others.

The net farm income results from maize, wheat, barley, dry beans and lucern are at the lower end of the spectrum compared with ground nuts, cabbages, potatoes and grapes. The farmer has thus many options available to choose from in deciding which crops to rotate with the winter cereals.

Crop rotations

The gross margins for each crop in a particular planned rotation must be compared to see if the input costs over several cycles makes economic sense. In the Southern Free Sate and Northern Cape irrigation scheme areas a continuous rotation of maize, ‘popcorn’ maize and wheat or barley, as practiced in the Taung area has been followed for many seasons. The production of barley as a winter cash crop is largely determined by the limited volume of contracts made to supply to the beer brewers in South Africa.

The plant residues between each crop, whether maize or wheat, were burnt after harvesting immediately followed by cultivation, spraying for weeds and planting. This practice resulted in over 100 kg of potassium a year being removed from the soils.

The plant residues between each crop, whether maize or wheat, were burnt after harvesting immediately followed by cultivation, spraying for weeds and planting. This practice resulted in over 100 kg of potassium a year being removed from the soils.

Soils tests showed that an increased amount of potassium for the next crop were required to compensate for this loss over time. The increased potassium, although a very expensive component of fertilisers, resulted in reducing the tendency of ‘popcorn’ maize to break or lodge before harvest. The results gave an increase of 1,5 t/ha to 2 t/ha increase in maize yields coupled with the correct amount and type of nitrogen applied.

Maize yields of 14,5 t/ha and wheat yields of 8 t/ha to 10 t/ha have been realised in one production year from the same pivot area.

Centre pivot irrigation farmers started introducing minimum tillage into different rotations well over 20 years ago. Some farmers have only recently stopped burning their wheat stubble in the Orange River. A rotation of soybeans and maize is common in KwaZulu-Natal within a well-managed minimum tillage environment. The management of the plant residues differs depending on the climate and depth and the quality of tilth and humus that happens over time in well managed soils.

The build-up of plant residues in a soybean and wheat rotation or maize and wheat rotation can really be a problem where only the very best and strong planters can operate in the heavy unbroken down stubble between continuous crops within an annual double cropping rotation. Management of this situation has resulted in farmers reverting back to the burning system which might be of immediate benefit but unsustainable over the longer term.

A solution to the excess stubble problem is the baling of the maize, wheat or barley residues between crop changes. With the short planting windows in an annual double cropping programme there must be enough baling capacity to do the job in time. On a 60-hectare pivot this implies the removal of 300 to 480 tons of wheat straw or maize residue per ha per year. Over time this will also result in a huge loss of potential plant nutrients. Farmers who compost this residue and spread this back onto the pivot lands can achieve over 16,5 t/ha average yield for maize and 10 t/ha for wheat production.

A solution to the excess stubble problem is the baling of the maize, wheat or barley residues between crop changes. With the short planting windows in an annual double cropping programme there must be enough baling capacity to do the job in time. On a 60-hectare pivot this implies the removal of 300 to 480 tons of wheat straw or maize residue per ha per year. Over time this will also result in a huge loss of potential plant nutrients. Farmers who compost this residue and spread this back onto the pivot lands can achieve over 16,5 t/ha average yield for maize and 10 t/ha for wheat production.

Most farms or farming operations have more than one pivot. If there are enough pivots a rotation system introducing a fallow season either in winter or summer can be of benefit to the existing production pressure on fertility and the development of an improved soil profile and tilth. It also gives management some space in which to do improved planning for improved workflow and lessens the requirement for an ever-increasing investment in large tractors and implements.

Other considerations

The planning required for the winter crop production must also take into consideration the irrigation scheduling required for each crop using SAPWAT or other programmes that help the farmer plan the required irrigation per day or cycle for maximum crop water efficiency related to the evapotranspiration rates experienced in your production area.

The planning must also incorporate the lowest cost usage pattern, in the day or night time Escom rates, to save on electricity costs. A proper programme to control weeds which can build up depending on the crops planted within the rotation system must also be considered and used.

Conclusion

It is evident that the planning of a rotational cropping programme on a single pivot is much simpler than planning for a farmer that is running five pivots or more in a diversity of micro production areas. In this case the introduction of lucern and other pastures, especially where small or large livestock are integrated into the long-term planning cycles can be of great advantage. The lucern or other pastures part of the cycle will assist in building soil fertility and structure and take the pressure imposed on management off the intensive continuous cropping cycle.

There are so many options available, one has to choose a system that suits individual farm managers and the special production area, climate and availability of markets for clients, corporates or co-operatives that support and purchase the products you plan to produce near you.

Article submitted by a retired farmer.

Publication: December 2018

Section: Pula/Imvula