Planning your forage crop

March 2020

Cultivated forage crops are usually planted to complement natural grazing and field crop residue. Most crops are grazed or used to make hay or silage. When grazed, it can be used in a green state when it is actively growing or as foggage (standing hay) after the crop has matured. In the case of hay or silage the feed is preserved to be used at a later stage as a feed supplement or when feed is scarce.

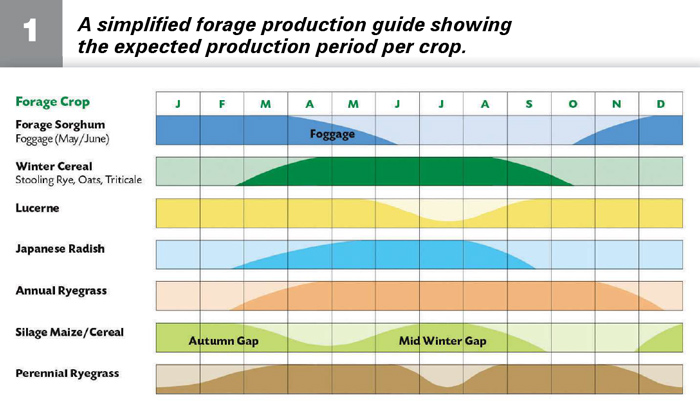

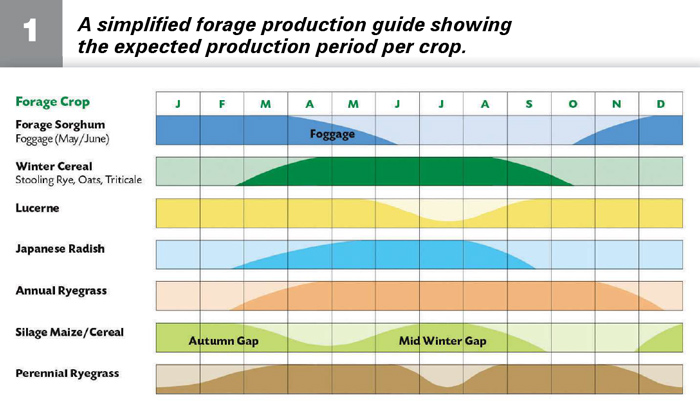

Crop options for grazing or foggage include the following:

- Summer crops: maize, forage sorghum, perennial grasses e.g. smuts finger and weeping love grass and lucerne.

- Cool season crops: ryegrass, Japanese radish, oats, triticale and stooling rye.

In the case of crops for hay or silage, the following crops can be considered:

- Hay production: teff, weeping love grass and lucerne.

- Almost any crop is suitable for making silage, but the least complicated crop by far, is maize as it is widely adapted, easy to cultivate and least complicated to ensile.

PRODUCTION PLAN

In developing a production plan suited to individual production systems several considerations need to be well-thought-out. These include which pastures would be best suited, economies of scale as well as the end-use of the pasture. All these considerations and their implementation will ultimately affect the profitability of the enterprise.

- The choice of species and variety would depend on the soil type, the availability and efficiency of irrigation, the climate and for which type of animal production purpose the pasture will be used. For example: Is there a need to plug the autumn quality gap? Is the pasture required for intensive animal production e.g. milk production, finishing of weaners or lambs, or is it required to maintain the condition of the breeding stock?

- Extensive dryland pastures usually require a long recovery period between grazings. Some pastures respond to rotational grazing better than others.

- Fertilisation practices should be geared to the pasture’s potential within the constraints of moisture availability (rainfall and/or irrigation) and soil type. Take a soil sample and have it analysed in order to correct the basic fertility before planting.

Once the basic fertility of the soil has been rectified, then fertilisation should be based on nutrient removal. A ton of grass hay or silage dry matter (DM) taken off a pasture will remove approximately 20 kg of nitrogen (N), 15 kg of potassium (K) and 3,5 kg of phosphorus (P). Legumes will remove more potassium and phosphorus, but well nodulated legumes can make a meaningful contribution towards the nitrogen needs of a pasture.

Up to 85% of the potassium is returned to the pasture via the grazing animal, but in the case of nitrogen, most is lost and only about 30% is utilised by the plant. Nitrogen fertiliser guidelines in this article are for zero grazed pastures (total removal of material). If pastures are grazed the recommended nitrogen application could be reduced.

- Intensive pastures, particularly those under irrigation, can cause internal parasite and fungal disease problems. An up-to-date dosing programme should be included in the plan, and in the case of sheep and dairy cows there should be foot rot preventive measures.

- Annual forage crops such as sorghum, millet, Japanese radish or the forage cereals (oats, triticale and stooling rye) should be grown as a supplementary source of feed. For example: Whilst perennial pastures are being established or when insufficient winter grazing is available from irrigated lands, the cereals can be sown on dryland.

- Mid-February to March/April are usually the most suitable months for pasture establishment, because there is less competition from weeds which must be controlled during the preceding months. The soil moisture status is usually better at this time of the year. Prepare a fine, firm and weed-free seedbed. For economic reasons, plant as early as possible (February/March).

- Pastures are preferably sown in narrow rows of about 180 mm for irrigated and intensive pastures to 0,9 m rows for extensive dryland pastures (e.g. forage sorghums). Speak to your Pannar representative or agronomist for a tailor-made recommendation. Seed that is broadcast and rolled will also result in a well-established pasture. The individual plants are not as robust as in a row planted pasture. It is recommended to plant pastures in rows in the drier areas.

- All pastures will benefit from a good rolling after sowing. Small seed in particular should be well rolled, and the soil of some soil types should be rolled before sowing as well. Only the larger seeds need to be buried at sowing, the small seeds should only be pressed into the soil.

- Newly established pasture should not be grazed too soon, it must be allowed to develop a good root system. Annuals are generally only ready for grazing 6 to 8 weeks after sowing, and perennials 8 weeks or more. Perennial pasture will take up to two years to reach full production. Heavy grazing after establishment should be avoided at all costs.

- If weed control is necessary in a newly established pasture, the first option should be a mower, and only if the weeds continue to be a problem, should a selective herbicide be used.

- The costs of establishing a pasture are high, and therefore attention to detail, particularly when establishing perennial pasture, will more than compensate for the effort involved.

Publication: March 2020

Section: Pula/Imvula