August 2017

Similar to their influence on human health, mycotoxins are known to cause many animal diseases (mycotoxicoses) and negative health effects. These factors also severely impact the economics of livestock and animal feedstuff trading.

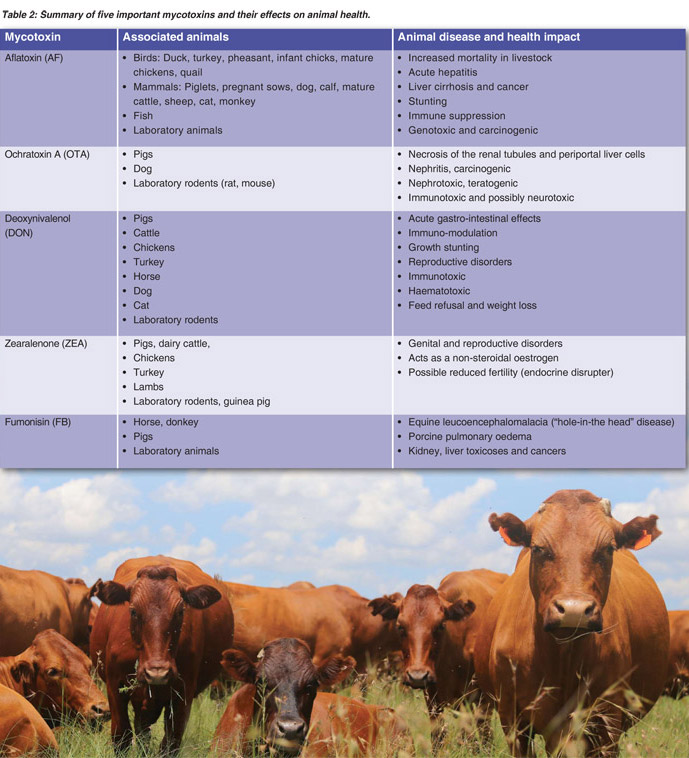

All the mycotoxins that are important in human health (aflatoxin, fumonisin, deoxynivalenol, zearalenone and ochratoxin A) are also important in animal health, but their disease effects differ greatly from human symptoms, as well as between different animal species (Table 2). Agricultural livestock and domestic animals (cats, dogs, etc) can be exposed to mycotoxins either through processed feedstuffs which contain contaminated grain or other agricultural by products, or by grazing on infected forage, reject maize cobs, contaminated cereal stalks and hay in the field. Other animal mycotoxicoses and their associated fungi, which are often associated withfield grazing in South Africa are: Ergotism (Claviceps species); stachybotryotoxicosis (Stachybotrys); facial eczema (Pithomyces); lupinosis (Phomopsis); and diplodiosis (Stenocarpella species).

In the South African maize milling industry, the “chop” milling fraction is widely used in animal feedstuffs and contains the highest levels of mycotoxins of all the different milling fractions. When highly contaminated maize batches are milled, then the resultant “chop” fractions could result in severe animal health effects if not blended with other less contaminated batches or other raw materials. In many cases, the cheapest and most contaminated material is used in animal feeds in the hope that no disease effects will be noticed, especially when no mycotoxin tests have been done on raw materials, such as cheap imported grain. This has often led to sudden animal deaths in products such as processed dog foods.

Animals exposed to contaminated feed can lead to acute or chronic diseases that will impact on livestock productivity. In some instances, disease symptoms and effects are hidden and may only become evident over time through altered growth patterns, reduced production and reproduction, as well as increased susceptibility to other infectious diseases. The co-occurrence of different mycotoxins in finished feeds (different batches of raw materials mixed to produce a final product), is a major concern as these can exert additive effects which makes the diagnosis of particular mycotoxicoses extremely difficult.

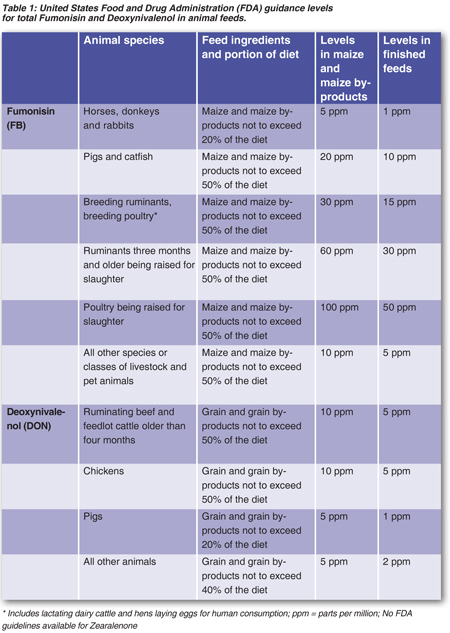

Livestock most vulnerable to mycotoxins are pigs to deoxynivalenol and horses to fumonisin, whereas the co-occurrence of these two mycotoxins would have even more serious consequences on both these animal species. The guidance levels set by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for fumonisin and deoxynivalenol are generally accepted worldwide and in the South African animal feed industry to protect livestock against mycotoxin risks (summarised in Table 1).

In our next and last article in this series, we will be focussing on methods to reduce mycotoxin exposure in humans and animals. It has, however, been found in several cases that when dealing with animal mycotoxicoses, the quickest and best way to reverse many disease situations is to immediately withdraw any suspect feedstuff from the affected animals’ diet, or to remove the animals from a field that might contain contaminated forage or leftover maize cobs.

As it is impossible to deal with every mycotoxin issue in full in this article, it is advised that you consult either a veterinarian, or an extension officer or this article’s authors to obtain more information on specific animal diseases and symptoms which might be linked to mycotoxins.

Article submitted by HM Burger and P Rheeder, Mycotoxicology and Chemoprevention Research Group, Institute of Biomedical and Microbial Biotechnology (IBMB), Cape Peninsula University of Technology (CPUT). For more information, send an email to Burgerh@cput.ac.za. or RheederJP@cput.ac.za.

Publication: August 2017

Section: Pula/Imvula