Methods to reduce mycotoxin exposure

September 2017

In the final article of our series on mycotoxins, we will describe methods to reduce mycotoxin production in commodities and human exposure to mycotoxins.

In the final article of our series on mycotoxins, we will describe methods to reduce mycotoxin production in commodities and human exposure to mycotoxins.

As mentioned before, mycotoxins are very stable and can only be partly removed. Crops produced for commercial purposes and the production of food and feed, have the advantage of being regulated for mycotoxins using specific mycotoxin safety levels and the monitoring of product quality. Also, the commercial crop production industry has access to advanced and expensive technological methods.

For the sake of this article we will concentrate on simple and affordable methods to reduce mycotoxin exposure such as 1) good agricultural practices (pre-and post-harvest methods), 2) hand sorting and washing, 3) winnowing, shelling, dehulling and milling, and 4) diet diversification (including a variety of foods in the diet).

Good agricultural practices

Good agricultural practice (GAP) is very important to agriculture, both commercial and subsistence farmers, in order to guarantee and maintain the lowest mycotoxin levels possible in cultivated food crops.

Pre-harvest methods

- Implementation of a crop rotation schedule. Wheat and maize are particularly susceptible to Fusarium fungi and these two crops should not be used in rotation with each other. Rotation crops such as potato, vegetables and dry beans, should rather be used.

- Adequate preparation of the seed bed for each new crop by ploughing under or by removing old crop debris that may also be affected by the relevant fungi. No-till and other integrated pest management practices may be required in the interests of soil conservation (commercial; subsistence application).

- Utilise soil tests to determine if there is a need to apply fertiliser and/or soil conditioners to assure adequate soil pH and plant nutrition to avoid plant stress, especially during grain development (commercial application). Subsistence farmers should apply livestock manure to their fields to enhance stubble breakdown, improve the soil structure and aid in plant nutrition (subsistence application).

- Use seed that has been developed for resistance to infecting fungi and insect pests, and recommended for a specific area (commercial application mostly).

- Crop planting should optimally be timed to avoid high temperatures and drought stress during the period of pollination and seed development (commercial; subsistence application).

- Avoid overcrowding of plants by maintaining the recommended row and plant spacing (commercial

- application mostly).

- Minimise insect damage and fungal infection by proper use of registered insecticides, fungicides and other appropriate practices within an integrated pest management programme (commercial; subsistence application).

- Control weeds in the crop mechanically or with the use of registered herbicides or other safe and suitable weed removal/eradication practices (commercial; subsistence application).

- Minimise mechanical damage to plants and fruit during cultivation/farming (commercial; subsistence application).

- Ensure that irrigation is applied evenly and that all plants in the field have an adequate supply of water. Excess moisture during flowering makes conditions favourable for the infection by Fusarium fungi; thus irrigation during flowering and crop maturation should be avoided (commercial application mostly).

Post-harvest methods

- Harvest grain at low moisture content and full maturity, unless under extreme heat, rainfall or drought conditions (commercial; subsistence application).

- Ensure that farm personnel are adequately trained and that all farming equipment is kept clean and functioning properly, to minimise damage to plants and the harvested crop (commercial; subsistence application).

- Containers and vehicles to be used for collecting and transporting the harvested crop from the field to drying and/or storage facilities, should be clean, dry and free of insects, soil and visible fungal growth (commercial; subsistence application).

- Determine crop moisture levels immediately after harvest. Where possible, dry the crop to the recommended moisture content for storage. Cereals should be dried in such a manner that damage to the grain is minimised and moisture levels are lower than those required to support mould growth during storage (generally less than 14%). Sun drying of some crops in high humidity may result in fungal infection. Avoid piling or heaping of wet, freshly harvested crops (commercial; subsistence application).

- Freshly harvested cereals and nuts should be cleaned or sorted, where possible, to remove damaged kernels/nuts and other foreign material (commercial; subsistence application).

- Storage facilities must be dry, well-vented structures that provide protection from rain, surface or ground water, protection from pests and birds, and protected from extreme temperature fluctuations (commercial; subsistence application).

- Ensure that storage bags are clean and dry. Filled bags should be stacked on pallets or a system with a water-resistant layer between the bags and the floor (commercial; subsistence application).

- The relevant mycotoxin levels in harvested crops should be monitored when needed, using appropriate sampling and testing methods (commercial application).

Hand-sorting and washing of grains

Hand-sorting and washing of grains

Hand-sorting or separation of crops prior to storage or cooking, is a common practice in many African countries such as West Africa (Benin), Nigeria, Tanzania and Southern Africa. Traditional food processing methods such as hand-sorting form a simple and inexpensive post-harvest prevention method to reduce mycotoxin contamination and exposure.

Several studies conducted in Africa among maize subsistence farming communities indicated that the separation of visibly damaged (including broken), discoloured and obviously mouldy maize kernels from visibly good-for-eating kernels reduced aflatoxin and fumonisin mycotoxin levels.

A simple method of hand-sorting and washing has shown that it can reduce the fumonisin mycotoxin levels in home-grown maize by 84%. Recently, a laboratory-based study using the hand-sorting, and an additional density separation step followed by the washing of the sorted good maize, showed a reduction in fumonisin levels of 98% in good maize.

An educational booklet has been developed to teach maize-subsistence farmers how to sort the maize kernels into visibly good maize (Photo 1 - 2). Then follows a step whereby clean drinking water is added to the maize, enough to cover all the maize kernels (about two fingers above the surface of the maize kernel layer). Any material floating on top of the water is then removed and finally the maize kernels are slowly mixed with the water and left to stand for about 10 minutes.

The maize is now ready for cooking; remember to throw away the kernels and any other material that was removed from the good maize during the sorting and washing step. The water and the kernels or material removed contains most of the mycotoxins and are harmful to both human and animal health.

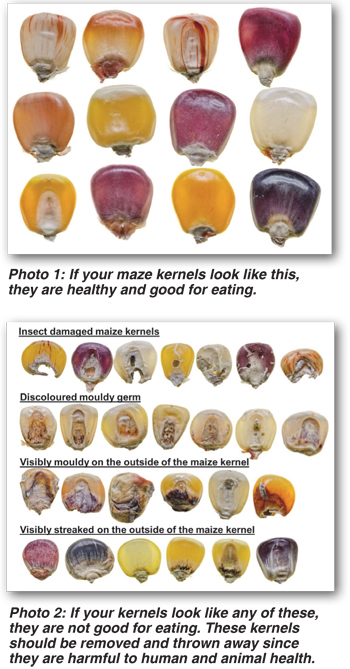

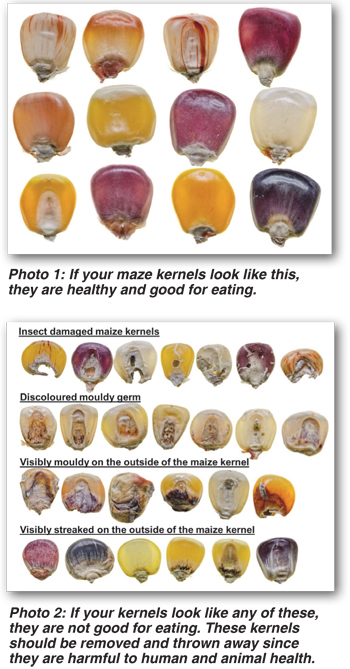

What does healthy maize kernels look like?

Visibly good quality maize kernels that is healthy for eating should be shiny or bright, have no stains or marks and should also be intact (Photo 1).

What does unhealthy maize kernels (that should be removed) look like?

Visibly good quality maize kernels that is healthy for eating should be shiny or bright, have no stains or marks and should also be intact (Photo 2).

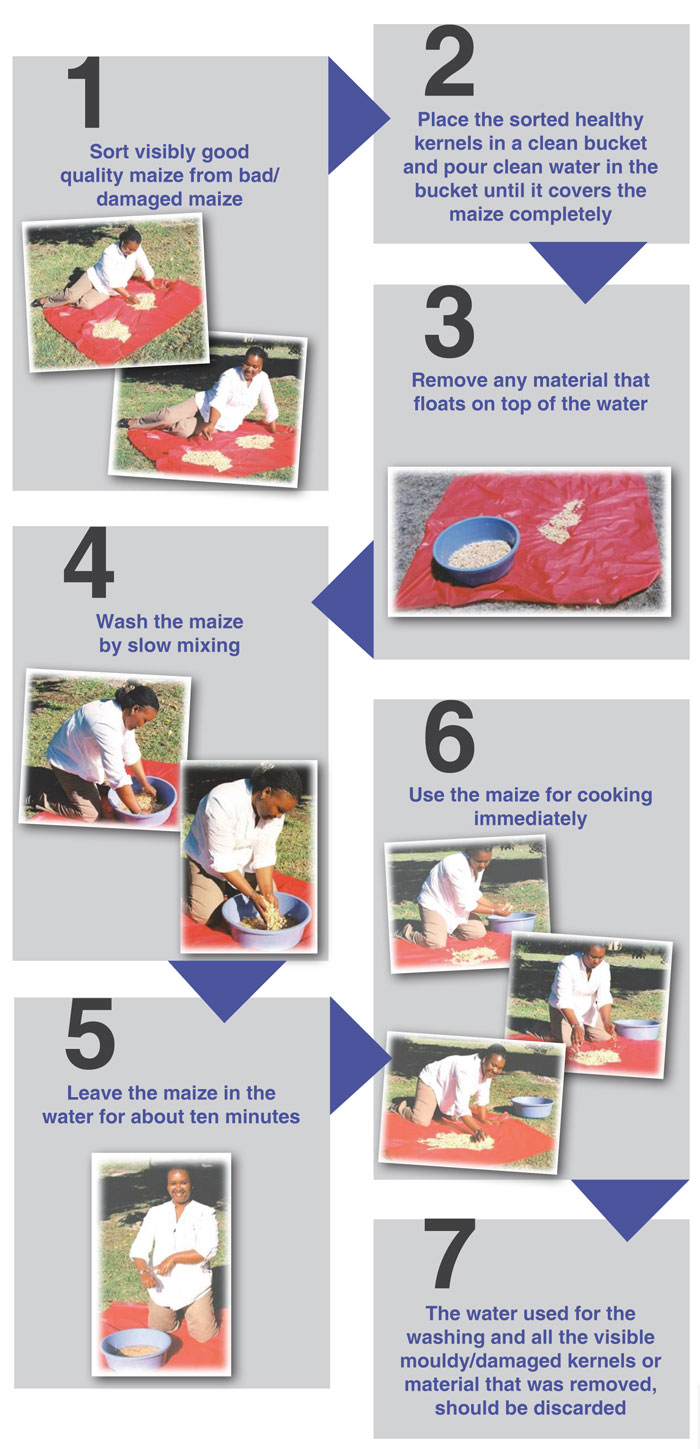

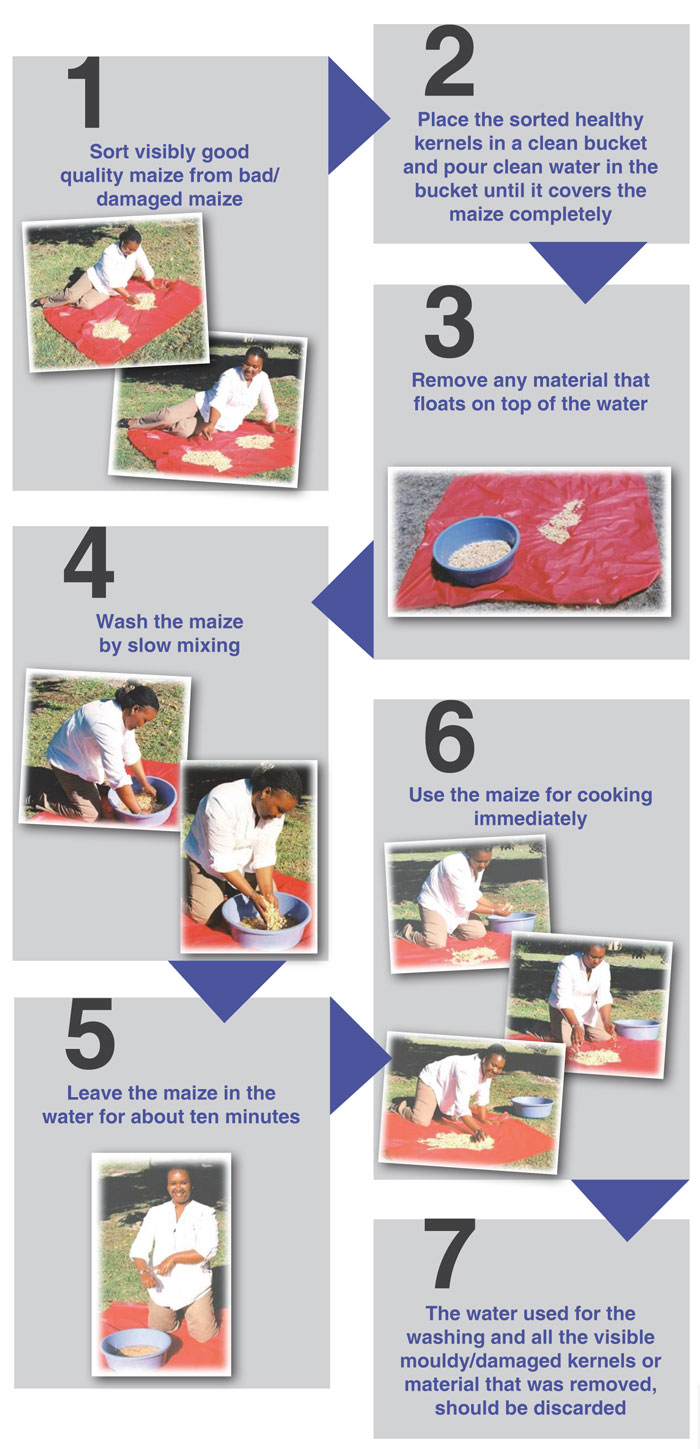

How to sort and wash in seven steps

Step 1: Sort visibly good quality maize from bad/ damaged maize.

Step 2: Place the sorted healthy kernels in a clean bucket and pour clean water in the bucket until it covers the maize completely.

Step 3: Remove any material that floats on top of the water.

Step 4: Wash the maize by slow mixing.

Step 5: Leave the maize in the water for about ten minutes.

Step 6: Use the maize for cooking immediately.

Step 7: The water used for the washing and all the visible mouldy/damaged kernels or material that was removed, should be discarded.

Diet and crop diversification to ensure variety in the diet

Diet diversification is all about the availability, access and use of foods that are nutritious (keeps the body healthy and helps with growth and development) all year around. This can be done by changing the type of crops that are planted, including different kinds of healthy foods in the diet and the preparation and processing of foods in the kitchen.

The following is a summary of some food based activities that can promote diet diversity:

- Promote the mixing of crops and/or integrated farming with different crops.

- Introduction of new crops (such as soybean).

- Promotion of home gardens.

- Small livestock raising such as chickens.

- Promotion of improved safeguarding and storage of fruits and vegetables to reduce waste and post-harvest losses.

- Nutrition education to encourage the consumption of a healthy and nutritious diet all year round.

Conclusion

Finally, we conclude with the South African Food Based Dietary Guidelines to ensure a healthy diet.

- Enjoy a variety of foods.

- Be active!

- Make starchy foods part of most meals.

- Eat plenty of vegetables and fruit every day.

- Eat dry beans, split peas, lentils and soya regularly.

- Have milk, maas or yoghurt every day.

- Fish, chicken, lean meat or eggs can be eaten daily.

- Drink lots of clean, safe water.

- Use fats sparingly. Choose vegetable oils, rather than hard fats.

- Use sugar and foods/drinks high in sugar sparingly.

- Use salt and food high in salt sparingly.

References

- JF Alberts, M Lilly, JP Rheeder, H-M Burger, GS Shephard and WCA Gelderblom. 2016. Technological and community-based methods to reduce mycotoxin exposure. Food Control.

- The Nutrition Information Centre of the University of Stellenbosch(NICUS), http://www.sun.ac.za/english/faculty/healthsciences/nicus/how-to-eat-correctly/guidelines/food-based dietary-guidelines

Article submitted by HM Burger and P Rheeder, Mycotoxicology and Chemoprevention Research Group, Institute of Biomedical and Microbial Biotechnology (IBMB), Cape Peninsula University of Technology (CPUT). For more information, send an email to Burgerh@cput.ac.za. or RheederJP@cput.ac.za.

Publication: September 2017

Section: Pula/Imvula

In the final article of our series on mycotoxins, we will describe methods to reduce mycotoxin production in commodities and human exposure to mycotoxins.

In the final article of our series on mycotoxins, we will describe methods to reduce mycotoxin production in commodities and human exposure to mycotoxins. Hand-sorting and washing of grains

Hand-sorting and washing of grains