October 2017

This article is the 28th in a series of articles highlighting crop species that can play an imperative role in conservation agriculture (CA)-based crop-pasture rotations.

Besides improving the physical, chemical, hydrological and biological properties of the soil, such species, including annual or perennial cover crops, can successfully be used as animal feed.

Livestock production systems are in many ways dependent on the utilisation of forage species, or pasture ley and cover crops (used interchangeably in this article), and can therefore become an integral component of CA-based crop-pasture rotations. To qualify as a pasture ley crop, a plant species must fulfil the requirements of a dual-purpose crop, i.e. it must be functional for livestock fodder and for soil restoration.

This article aims to discuss the economic benefits and returns of a ‘pasture ley’ crop incorporated into cropping systems. The term ‘pasture ley’ can include a variety of annual or perennial species, legumes, grasses or root forage crops used in short or long-term rotations. It is therefore important to distinguish between a short-term and long-term ley cropping system.

The economic impact of pasture ley crops on crop production systems

Integrating pasture ley crops into a crop production system has been proven to have significant merit, which often reflects in short- and long-term economic returns. The ultimate integration of crop and livestock production systems can enhance the environmental and economic sustainability of such a CA system.

By using a ley cropping system, cash crops such as wheat, maize and soybeans can be rotated in short- or long-term cycles with legume or grass pastures with the added economic value to a livestock production system.

These integrated systems create biological and economic synergies between crops and livestock enterprises. This article aims to address the question: ‘What are the economical and biological advantages of such a pasture ley cropping system as part of a CA system as compared to alternative methods of crop and livestock production?’

Economic consideration for using pasture ley cropping systems

Producers are not accustomed to calculating the profitability of pastures to compare their profitability to grain crops. This becomes extremely important when a decision needs to be made whether or not to incorporate a pasture ley crop into a grain cropping system.

Pastures can be regarded as a medium- to long-term investment and management change and it is important to take into account the current and future prices for crops and livestock. It is therefore imperative that one continues to monitor grain prices before considering planting a pasture for three or more years on cultivated land.

Of critical importance, however, are the improvements in a range of ecosystem services, especially soil health, associated with pasture ley crops, which results in a steady improvement in yield and profitability over the medium to longer term.

This is further influenced by a steady decline in input costs, such as agro-chemicals and diesel. The significant fluctuations in grain prices resulting in a subsequent long-term price decrease (in real terms) should be another main motivation to integrate crop, pasture and livestock production systems.

World grain prices are volatile and decreasing in real terms i.e. when inflation is removed, with the economics of pastures versus grain and forage crops also continuously changing.

Concept of pasture ley cropping

A ley farming system is a system in which grasses and/or legumes are grown in short or long-term rotations with cash crops, with the intention to intensify the crop-fallow system in a sustainable manner. This grass or legume pasture ley crop serves as a resting phase from cash cropping through a ‘green fallow’ (compared to a ‘black fallow’ of bare soil).

This green fallow with pasture ley crops serves the function of restoring soil health after long periods of continuous cropping with grain cash crops and provides the additional value of grazing or hay for cattle. Grass pastures in particular have the ability to suppress other weed species reducing the cost of chemical control.

Once this pasture ley crop has served its purpose, it can be killed chemically followed by a no-till practice to plant cash crops. Pasture ley crops containing a legume are extremely valuable and address the widespread deficiency of nitrogen for both plant and animal production.

The incorporation of legumes into grass pastures, or the solitary use of legume pastures are valuable, because they establish easily – especially after a short crop phase. These legumes contribute to appreciable levels of biological N in the soil and particularly to subsequent crops.

These legume crops are also easily controlled as required in the crop phase and they contribute to good lightweight gains in cattle grazing systems. Prospects for widespread commercial use of ley systems are considered as a strengthening of the economic viability of grain cropping in various regions of South Africa.

Biological benefits

Producers urgently need to manage a number of serious environmental challenges facing grain crop production systems, such as soil health decline, soil erosion, biodiversity loss and climate change.

Ley crop systems have the ability to stop and reverse all these detrimental processes. It can restore critical ecosystem functions and services by improving soil organic matter, fertility and soil structure with the establishment of strong, living root systems.

The soil fertility improvements, especially the addition of nitrogen from legume pastures through N fixation, make the following cropping phase more profitable. Research has shown that a good legume pasture stand can contribute the equivalent of 10 kg to 90 kg N/ha (Jones et al. 1983; McCown et al. 1986).

It improves water infiltration and –storage, leading to stable higher yields of the following cash crops, even during dry periods. With low overhead costs, a pasture ley crop can still ensure good profits per hectare, while improving the various ecosystems such as soil and reducing the risks.

Economic comparisons, analysis and value

When considering the alternative use of cultivated land, especially for a forage cover crop or short or long-term pasture, it is important to calculate the potential income and subtract the estimated cost of production.

For example, livestock running costs and profits should be compared to grain crop costs and profits. The costs of running livestock on the pasture ley crops can be considerable if livestock is bought and brought onto the property, specifically to fatten them on forage or pasture. When livestock is already on the property, at least 50% of the transport costs are covered and the capital required to purchase livestock does not have an immediate cash flow impact.

It should be noted that in most cases breeding cows are less profitable than fattening weaner calves. It is also difficult to calculate profit from dairy cows, since pasture quality remains the determinant factor on a year-on-year basis.

Supplementing livestock on winter pastures and proposed grazing system costs (fencing and drinking water provision) also need to be included as a cost item on the overall farm feed budget. Additionally, overhead costs of machinery, labour and administration need to be considered.

Fortunately, pastures have much lower costs of depreciation and labour. With changes in the labour, machinery and administration costs, it is better to examine the income potential and costs on a whole farm basis, rather than per hectare and over the short- or long-term period of the pastures or forage cover crops. If there are no major changes in the aforementioned costs, the profit per hectare is a good starting point.

The subsequent soil health improvement from a pasture ley crop is not easily quantified and mostly excluded from the profit calculation. It can possibly be realised in the improved profit gained from the successive grain crop production. It is also essential that realistic assumptions be made when introducing pasture ley crops, i.e. the possibility of a dry year when forage yields are lower and the grazing periods shorter.

Old cultivated lands or marginal lands could possibly have low nitrogen levels and will require a fertiliser input that can potentially make the system uneconomical. This scenario does provide the opportunity to introduce a legume which can over time contribute to the soil nitrogen levels.

Hypothetical scenario (model prediction)

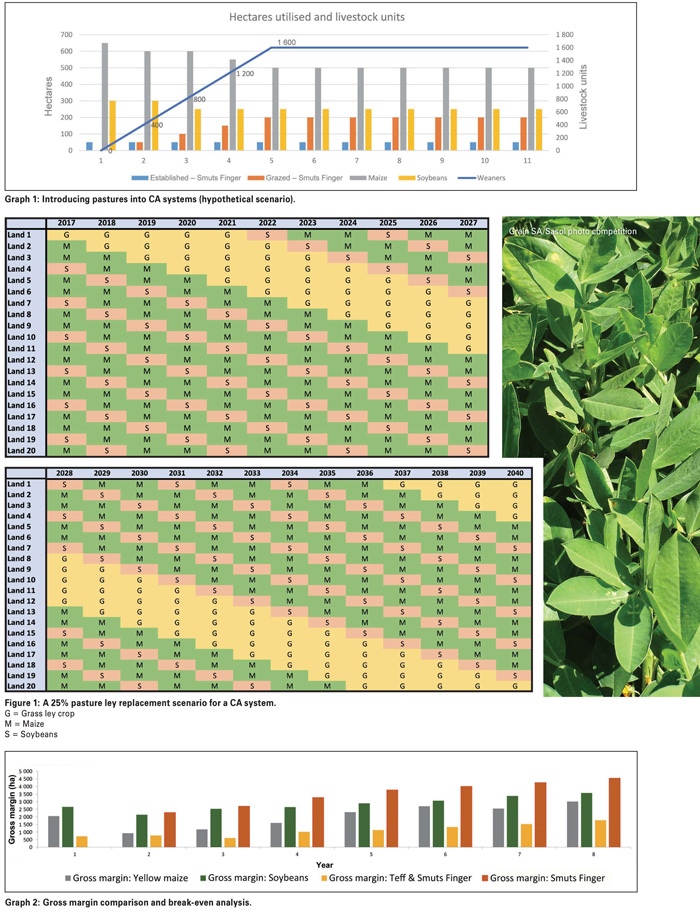

This scenario assumes that a producer has 1 000 ha of cultivated land with 75% under cash crops (in this case maize and soybeans) and 25% under Smuts Finger grass planted pasture (Graph 1).

In year one, 650 ha of maize are planted, 300 ha of soybeans and 50 ha of Smuts Finger grass (with no grazing in year one). In year two the process is repeated, except that the first-year grass can be moderately grazed.

This conversion process is repeated so that by year five, at least 25% of the cultivated land is planted to a grazing crop. It should be stated that in an ideal CA rotation system a third crop such as sunflower will have to form part of the cash crop rotation.

Planting two crops for a successive 19 years is not regarded as sustainable in CA. Ideally, annual cover crops should be included every third year.

A practical layout is represented in Figure 1, where a 1 000 ha of cultivated land are hypothetically broken down into 50 ha fields (known not to be the case, but the concept is illustrated). The 1 000 ha are therefore broken down to 20 fields.

From this process it is illustrated that a cash crop to grass conversion factor of 75%:25% is considered, fields would be planted to grass in year one, grazed for five years and re-introduced to cash crop production for 15 years, to then only be planted to grass again in the 20th year.

This conversion process will have economic implications, with the cash flow restriction probably being the most obvious one, since the capital investment in an intensive grazing rotation is higher than conventional cash crop production.

From Graph 2 it is evident that the grazed Smuts Finger pasture’s gross margin per hectare can break-even in year three, and from there on, it has a higher return per hectare than that of maize and soybeans.

It should be noted that this model prediction is based on a typical farm in the North Western Free State, where rainfall variability remains to be a key risk factor (i.e. lower yield assumptions for maize and soybeans). With the inclusion of pasture in a cash cropping system (as in this particular example) at least 25% of the total area planted has a risk mitigating impact.

Management of pasture ley crops before the successive grain cropping cycle

As part of the proposed pasture ley cropping system, no-till planting of the crop is essential for reducing the risks of soil erosion. It is beneficial to plant directly into the plant residues, which consist of pasture material from the ley cropping season/s that has been killed with herbicide, one or two weeks before planting.

Intervals between the killing of the pasture ley crop and the planting of the successive crop should be short, otherwise the residues, especially legume residues with their low C:N ratio’s, will decompose very quickly. Grass ley pastures have the added advantage of taking up N rapidly during the early rains, minimising the leaching loss and then releasing it to the crop when killed by the herbicide.

Mixed grass and legume pastures are preferred from a grazing perspective compared to pure monospecific grass pastures. Crops grown after pure grass ley pastures (especially grass crops such as maize) could have yield restrictions due to an N-negative period and N-fertiliser levels should be adjusted accordingly (around 30% higher).

To prevent the grass component of the mixed pasture ley crop to dominate, judicious cattle grazing can be used to remove the larger grass canopy, which will benefit the legume component. When grazing ley crops in the dry season (winter), it is essential to leave sufficient well distributed plant cover on the soil surface for the successful re-establishment of either the pasture or the successive grain crop.

This is a key compromise that has to be reached between the needs of the animals and of the plants in the system.

Conclusions

Pastures are most likely to produce good profits compared to grain crops on a per hectare basis, especially on soils that have accumulated effects of land degradation which will increasingly limit the grain potential in future.

Secondly, pasture leys have significant benefits and improvements to ecosystems (especially soil health), which are not always quantified to emphasise the dual purpose of the pasture ley crop. However, the noticeable increases in grain yields after pasture ley crops will provide some reflection on their additional rand value, other than just the revenue generated from the pasture ley crop from cattle grazing.

Pasture ley crops improve the productivity and enhance the sustainability of mixed farming enterprises. For such systems to be effective, it is imperative to conduct ongoing on-farm research of these complex systems, especially to:

Overall, the positive attributes of an integrated crop- and pasture-based livestock CA system will facilitate the creation of a more sustainable grain production system.

For more information contact Dr Wayne Truter (wayne.truter@up.ac.za ), Mr Gerhard van der Burgh (gerhard@bfap.co.za ), Dr Hendrik Smith (hendrik.smith@grainsa.co.za ) or Mr Gerrie Trytsman (gtrytsman@arc.agric.za ).

References

Jones, RK, Peake, DC, and McCown, RL. 1983. The effect of various tropical legumes on nitrogen supply. Annual report 1982 - 1983, division of tropical crops and pastures, CSIRO: Australia. pp. 135 - 136.

Jones, RK, Dalgliesh, NP, Dimes, JP and McCown, RL. 1991. Sustaining multiple production systems 4.

Ley pastures in crop-livestock systems in the semi-arid tropics. Tropical grasslands 25, 189 - 196.

Lloyd, Dl, Smith, KP, Clarkson, NM, Weston EJ and Johnson, B. 1991. Sustaining multiple production systems 3. Ley pastures in the subtropics. Tropical grasslands 25, 181 - 188.

McCown, RL, Winter, WH, Andrew, MH, Jones, RK and Peake, DC. 1986. A preliminary evaluation of legume ley farming in the Australian semi-arid tropics. In: Haque, I, Jutzi, S and Neate, PJH (Eds) Potentials of forage legumes in farming systems of Sub-Saharan Africa. pp. 397 - 419. (ILCA: Addis Ababa.)

Wylie, P. 2007. Economics of pastures versus grain or forage crops. Tropical Grasslands 41, 229 - 233.

Publication: October 2017

Section: On farm level